I've been writing about goal-setting for years. It never made me an expert; I've just constantly wondered out loud about the best way to achieve what I want. When I sat down to finally write again a few weeks ago, though, I was determined to nail down my definitive take on goal-setting and never need to wonder again. But then, of course, I stumbled on a book that blew apart everything.

In Why Greatness Cannot be Planned - The Myth of the Objective, co-authors Joel Lehman and Kenneth O. Stanley confront the idea of ambitious goals (or, as they call them, objectives). We're talking about the goals that are so large we don't even know the stepping stones to achieve them. There is no clear, singular path to building a billion-dollar company, becoming the voice of a generation, or even molding a room full of young minds. But the current consensus seems to be that you need to put your head down and inch your way to achievement.

Lehman and Stanley think differently. They believe that the most ambitious of goals end up being the most deceptive. Why? Because the more steps you need to take, the more opportunities appear for you to trip. With an infinite amount of paths to get to your particular slice of the future, you can't confidently judge if you're ever getting closer or further away from the goal. Or, more importantly, as Lehman and Stanley explain, if either of those directions is best.

Let's start at the beginning.

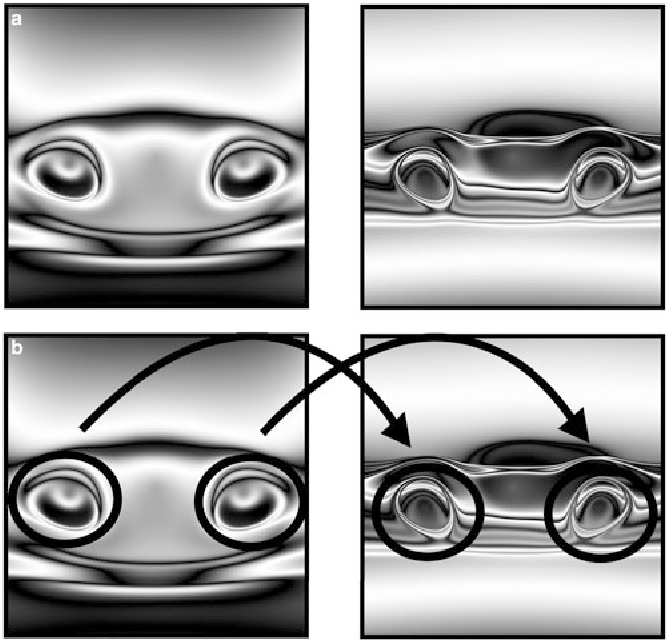

It's probably important to understand how Lehman and Stanley got to this idea. Both being AI researchers, they built a program called Picbreeder that allowed anyone on the Internet to choose an image from a grid that would then breed a whole batch of new images from their selection. In addition, Picbreeder allowed users to save and share their findings with the world and so others could pick up where they left off. It began with black-and-white blobs and, slowly but surely, users clicked their way to new, radical designs:

Why in the wide, wide world of sports is this relevant to goal-setting?

Well, originally, it wasn't. Picbreeder had no objective. There was no ultimate image to create. Users just clicked away, exploring an eclectic collection of imagery. But when Lehman and Stanley built an AI program to try and recreate the success of some of those colorful images above, it didn't work. As advanced as modern computing can be, it couldn't reverse-engineer a particular masterpiece.

It seems crazy, right? The users didn't do anything spectacular to stumble on the image of a skull or a car, they just clicked some other images to get there. But because Lehman and Stanley programmed AI with a specific objective, it could only seek out evidence of progress as it chose images to get there. Anything that didn't look like it was getting closer to the goal was thrown away. But sometimes a change you didn't expect is necessary to get where you might want to be.

Stanley offers a more specific example in the book when he describes how he was deceived by his own ambitious goal. Clicking through images, Stanley started to notice two round blobs that he thought looked like tires and he could click his way to becoming a car. But as he progressed with that objective in mind, he started to notice the possibility that those same round blobs could be the eyes of an extra-terrestrial. He ended up in a much different place than he imagined from the beginning.

Lehman and Stanley believe Picbreeder reveals the problem with ambitious goals. The co-authors wrote, "Our preoccupation with objectives is really a preoccupation with the future. Every moment ends up measured against where we want to be in the future. Are we creeping closer to our goal?"

The thing is we don't know. We can't know. Not everything is clear or linear. A failure to do one thing could teach you the skills you need to succeed somewhere else. An embarrassing mistake could lead to meeting the mentor of your dreams. Even an injury or illness could reveal something about yourself that you needed to learn. Lehman and Stanley wrote, "Sometimes the best way to achieve something great is to stop trying to achieve a particular great thing. In other words, greatness is possible if you are willing to stop demanding what that greatness should be."

This is some seriously spiritual shit. We're not machines, we're humans. We can't just punch in some goal coordinates and speed forward until we run out of gas. We're missing the point. When we're busy focusing so intensely on the future and where we want to be, we lose sight of the journey. It's like Alan Watts once said, “Making plans for the future is of use only to people who are capable of living completely in the present.”

The big idea here is not to wander the globe with no goals to your name. Instead, Lehman and Stanley think this simple AI program shows us that we should primarily seek out what interests us. Follow your nose. Click the image and see where it takes you. Be open to opportunities that allow more opportunities. Find the treasure.

Small stuff

It might also be that we get caught up in the ambitious altogether. We don't put enough value in the small stuff. Lehman and Stanley reminded me of one of my favorite XKCD comic strips titled Choices. In the strip, a stick figure stumbles through a void that opens in a corporate office. He floats through space only to find a version of himself that offers some advice for existence. In my ambitious and anxious 20's, I often resonated with a particular bit that now hits more deeply today:

“You’re curious and smart and bored, and all you see is the choice between working hard and slacking off. There are so many adventures that you miss because you’re waiting to think of a plan. To find them, look for tiny interesting choices. And remember that you are always making up the future as you go.”

I don't know if this is the last I'll write about goals. I still want to do certain things. I want to own my own business, level up in jiu-jitsu, and find a partner that loves bad movies and bad jokes as much as I do. But maybe I just need to find the right stepping stone. Or wander around, looking for treasure for a bit.

Needless to say, I think I found what I was looking for. I wanted to finally understand how to perceive goals and after all I guess I kind of did.

Happy hunting!